Canto 22 begins with a triumphant ascension from the fifth cornice, that of the hoarders and spenthrifts, with the help of the Angel of Liberality, and into the sixth, that of the gluttons. The soul now is infused with a new kind of craving: righteousness and justice. The Angel proclaims this advance through the Gospel declaration: "Beati, and with sitiunt and no more to end the phrase, his words accomplished this." The angel, in other words, by the proclamation of "Beati qui esuriunt et sitiunt justitiam" (Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness), he signals a sort of "graduation", but this one is marked by an ever-deepening desire, a thirst, for righteousness (the angel saves the reference to hunger for the cornice of the Gluttons).

At this point, the main theme revolves around desire. This theme forms the context for the conversation between Virgil and Statius. This theme of desire is heightened by Virgil's opening verse:

..."The love that's lit

By virtue must, once its flame is shown,

Kindle a love reciprocal to it

Virtue enkindles love, and that love finds its greatest fulfillment in "kindling" that same "recipororacal" to it, i.e. shared with another, in a communion that finds even greater fulfillment and consummation in the love of God. This is the end towards which Dante, now much lighter and "spritely", is moving, shedding all vestiges of self-love, or what St. Maximus the Confessor calls "philautia," that all-consumming obsession with the self and the satisfaction of its unruly passions and lusts.

This is what motivates Virgil's question to Statius in lines 22-24:

How could thy heart find room for covetise,

When thou hadst filled it with such treasure-trove

of wisdom, by thy pains and exercise?

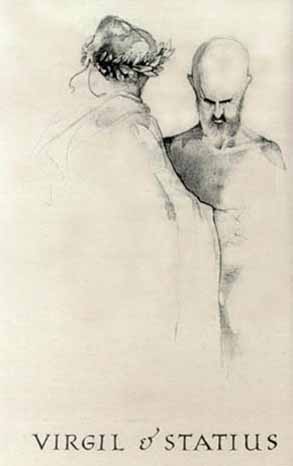

Statius responds with an affectionate statement about how Virgil's "every word...is a dear token to me of thy love." Here the new "Christian humanism", represented in Statius, acknowledges deep ties and sympathies with the best of the old pagan humanism, represented by Virgil. Statius further emphasizes this debt to Virgil in lines 64-69, where he likens Virgil to a man who, walking in darkness, nonetheless carries a lantern in at his back, lighting others to the "right way" (remember Dante's predicament at the beginning of the Inferno: "Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita...).

This is a rather peculiar image. What person, with any sense, would go about the dark with a lantern to his back? Yet this is the predicament that Virgil finds himself in as a pre-Christian pagan, and it is also the predicament of all those venerable sages in Limbo, Virgil's eternal home (Las Casas, in his debate with Sepulveda, called Aristotle a "pagan in hell who nonetheless had much good to say.") The non-Christian sage sheds light, but it is light that benefits not himself, but those who come after him, who have the benefit, like Statius, of Christian revelation. Or rather, it is that light of truth which he sheds that makes it possible for one like Statius to recognize the supreme truth-Christ, who is the Way, the Truth, and the Life.

This theme is especially emphasized in lines 70 through 80. Statius praises Virgil as the author of the Eclogues, especially the Fourth, with its promise that "to us...a new world is given, Justice returns, and the first age of man, and a new progeny descends from heaven." Virgil wrote these lines as a celebration of the impending birth of the son of Octavian, but nonetheless many Christian writers (especially the educated folk) interpreted these lines as Virgil unwittingly anticipating the birth of Christ. Statius, at least, is a beneficiary of this happy interpretation. It prepared him to hear "the new preachers" who combined these verses from Virgil with the Gospel, thus creating "a wondrous haprmony." The Gospel and classical poetry (Virgil) make a symphony: the natural virtues (prudence, justice, temprance and fortitude) with the theological virtues (faith, hope and love), reason with faith, nature with grace.

What does this mean for Dante the poet? As he nears the culmination of his sojourn in Purgatory, he now can count as his guide two masters: a pagan, and a Christian. In Dante's world, Statius has surpassed Virgil, since he has the hope of beatitude, perfecting the wisdom of Virgil in the truth of Christ. And now Dante sees the challenge before him. Learning much from Virgil, having made a long journey with him, learning from him, he will soon go to a place where his master cannot go. He must now take his art to the very center of deep heaven, into the very life of God.

But in the meantime, there is yet much to learn from the exchange between Virgil and Statius:

They walked in front, and all alone behind

I followed, listening to their words, which shed

Much light on poetry to aid my mind. (127-129)

Indeed, there is much to learn, especially as the theme of the cornice into which they are entering is the reorientation of desire. It is the cornice of the gluttonous, where a great feast of pleasurable delights awaits the eyes, but those who go through it must refrain from partaking. There is an even greater delight that awaits Dante: the Tree of Life, in the Garden of Eden, planted there at the age of man's first innocence. But even that will only increase his desire for the heavenly country, for the abode of God. Poetically, it also serves to move Dante-the-poet on to a greater aesthetic, going beyond Virgil (but not supplnting him, either), into the beauty beyond words of deepest heaven.